“Many who live with violence day in and day out assume that it is an intrinsic part of the human condition. But this is not so. Violence can be prevented. Violent cultures can be turned around. In my own country and around the world, we have shining examples of how violence has been countered. Governments, communities and individuals can make a difference.” - Nelson Mandela

The Silent Pandemic is a dynamic information portal dedicated to offering educational resources, links to help centres, the latest news coverage on related topics as well as a platform for those who need their stories to be heard.

Violence begets violence. According to the South African Research Chair in Human Capabilities, Social Cohesion and the Family, Professor Nicolette Roman, research suggests that violence and risk are potentially transferred across generations. “The link needs to be broken for South Africa to become less violent.”

The family is considered the key to address violence in society. However, for some, the family environment can be toxic. But we can be each other’s family. Communities can reach out to assist the most vulnerable.

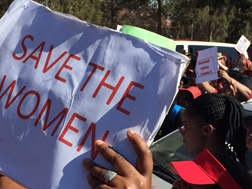

If you see or hear something that is not right, don’t stand by; stand up! Staying silent leads to violence. Break the silence, end the violence. If not you, who?

Should you require further assistance, want to assist, contribute resources, or share your story or comments, send an email to tsp@ofm.co.za.

Please note: this content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical, psychological or legal advice. Always seek the advice of a professional with regard to specific challenges you may be facing. Also, if you are struggling with some these issues yourself, some of this content may not be right for you, and could upset you. You may want to consume it with a trusted person.

Violence is a global phenomenon. According to knowledge hub saferspaces.org, more than a million people die each year as a result of self-directed, interpersonal or collective violence. This makes violence one of the leading causes of death for people aged 15 to 44 years.

For effective prevention of violence and crime, it is important to have a clear understanding of what violence is, and why it occurs, according to safterspaces.org. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or real, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal-development or deprivation.”

The WHO further differentiates between three main types of violence:

- Self-directed violence, with suicide as its most severe form, can have an effect of interpersonal violence.

- Interpersonal violence is defined to include "violence between family members and intimate partners, and violence between acquaintances and strangers, that is not intended to further the aims of any formally defined group or cause.

- Collective violence is defined as "the intentional use of violence by people who identify themselves as members of a group – whether this group is transitory or has a more permanent identity – against another group or a set of individuals, in order to achieve political, economic or social objectives."

There are also four general categories of violence: physical, sexual and psychological violence and deprivation or neglect.

Interpersonal violence can by its nature be physical, sexual or psychological, or it can be deprivation or neglect. Very often several types of violence exist together; they often overlap, interact and reinforce each other. For example, the nature of the violent act can be physical (harm to the body), while the effects can be psychological.

Physical violence does not only lead to physical harm, but can also have severe psychological effects: e.g. if a child is frequently victim of physical violence at home, or if a person is victim of severe physical violence, they can suffer severe mental health problems, and be traumatised as a consequence of victimisation.

Sexual violence can lead to physical harm. In most cases though, it has serious psychological effects. According to the WHO, victims of sexual assault have an increased risk of:

- depression;

- post-traumatic stress disorder,

- abusing alcohol,

- abusing drugs,

- being infected by HIV or

- contemplating suicide.

Psychological violence can lead not only to mental health disorders, but also to severe physical afflictions, such as psychosomatic diseases.

Deprivation or neglect can lead to physical as well as psychological problems: under-nourishment or malnutrition, for example, has direct effects on the health of a child or older person.

Myths: some examples people may not consider violence

- If parents or other caretakers do not comply with health-care recommendations for children, this is a form of neglect, and as such violent.

- Many forms of so-called parental discipline behaviour are in fact a form of violence. In many cases, it constitutes severe violence, including where children are hit with an object, burnt, kicked or tied up.

- Did you know that all forms of abuse are forms of violence, any form of child abuse, abuse of elderly persons or abuse among family members?

- Any form of corporal punishment at home or in school is a form of violence, and violates the child's right to physical integrity (as stated in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child):

- Did you know that more than one in four children in South Africa experiences times in childhood when physical violence at home occurs daily or weekly? Sticks and belt are often used, and children are often injured.

- Any form of verbal and psychological punishment is a form of violence, though not considered harmful. Examples include yelling and screaming at the child, calling the child names, cursing, refusing to speak to it, threatened abandonment, threatened evil spirits, etc.

- Despite redistribution of land and restitution, "forced displacements" still happen, often without legal persecution, and thus unpunished in South Africa. These are forms of severe violence.

- The misuse of power of a specific person can be a violent act, e.g., if one person with an official function misuses his/her power in order to make somebody do something.

This is not a form of structural violence, because there are concrete and direct personal relationships involved.

However, a society characterised by structural violence may make it more possible for these types of acts happen frequently and with impunity.

What is structural (indirect) violence?

Another categorisation of violence is particularly relevant for violence and crime prevention in South Africa: the so-called structural (or indirect) violence.

This additional category was developed by Johan Galtung, principal founder of the discipline of peace and conflict studies. Galtung distinguishes between direct violence, where an actor or perpetrator can clearly be identified (direct violence) and violence where there is no direct actor (structural violence).

Redressing structural violence requires political changes and changes in society, as well as changes in the structures and patterns that govern people’s lives. Structural violence follows other dynamics:

“The violence is built into the structure, and shows up as unequal power – and consequently as unequal life chances. […] if people are starving when this is objectively avoidable, then (structural) violence is committed.”

“Indicators of structural violence (are) exploitation, conditioning, segmentation, and marginalisation/exclusion.”

According to saferspaces.org, violence is an extremely complex and multi-causal phenomenon:

- South Africa suffers one of the world´s highest levels of inequality. More than poverty, equality breaks down social cohesion and trust. When people who are deprived live alongside others who have excessive wealth, their sense of injustice and anger is often increased.

- Although it is a country with rich natural resources, South Africa has high levels of poverty and many people cannot meet their basic needs because of insufficient income and the highly deficient delivery of basic services.

- One reason for this, and a problem still to be solved, is the chronically high unemployment in the formal sector.

- Employment dynamics affect not only the income but also the respect and status, involving social cohesion and economic opportunity.

- Social and political exclusion and marginalisation affect young people particularly, causing problems rather than opportunities.

- Government institutions fail to support a positive youth socialisation, e.g. within the education system.

- Masculine identities often promote the use of violence, meaning “a man has a right to be violent”.

- South Africa has one of the highest alcohol consumption levels per drinker in the world. Much of the worst violence occurs as a result of alcohol and drug abuse. Many victims are also rendered vulnerable by alcohol.

- Easy access to firearms contributes to high rates of armed violence.

The legacy of apartheid and colonialism serve as a background relevant to high violence and crime rates in the country today. This is a complex topic: colonial racial oppression over centuries, violent state repression and institutionalised racism under the apartheid system, as well as migrant labour and influx control systems adversely affecting family structures and social cohesion, and the impunity of criminals in the townships under apartheid, are just some aspects related to violence and crime.

In this context, a culture of violence is often cited as penetrating daily life everywhere. It does not mean the cultures in South Africa have a violent character, but violence has become a part of daily life.

A culture of violence means: a majority of children and young people grow up in an environment in which violence is part of daily life.

- Violence within families, between parents, and parents being violent towards their children;

- Violence at school and on the street, on TV and other media, video games glorifying violence;

- Violence as a means to deal with one´s feeling of inferiority or as a means to create a feeling of belonging, for instance to a youth gang;

- Violence of men against girls and women as part of expressing one's masculine identity; and

- Violence which has been considered by people supporting apartheid, and people fighting against it, as a 'legitimate means' to achieve one´s political purposes over decades.

“There is research that indicates that crime, and often violent crime, is a primary means for many young South Africans to connect and bond with society, to acquire “respect”, “status”, sexual partners and to demonstrate “achievement” among their peers and in their communities”.

In a culture of violence, violence is seen as a normal and inevitable part of daily life.

This can and needs to be changed, step by step.

According to saferspaces.org, violence is complex and its multi-layered nature can be seen when analysing the "actors in the play". It has different dimensions with regard to perpetrators as well as victims. Two important dimensions of violence are:

- the age dimension

- the gender dimension

Drawing on the WHO definition of violence, youth violence can be identified in three major types: self-directed, interpersonal and collective violence.

Youth violence is physical or psychological harm done to people - either intentionally or as a result of neglect - which involves young people as perpetrators, victims or both, or which is a potential threat to the youth.

The fact that in many countries children and young people up to the age of 24 account for 50% or more of the total population, as is the case in South Africa, highlights the enormous relevance of the topic.

Young people can be victims of violence. They have fewer defences against violence than adults. The young face violence during a period in their lives closely connected with identity-building and personal development; at a time when they are assuming roles and adopting the values and attitudes that will do much to shape later behaviour patterns.

Young people can be perpetrators. Violent acts of young people range from the use of violence to “solve” conflicts among peers, to criminal behaviour in urban areas and forms of group violence used by youth gangs.

When we look at the causes of youth violence, it becomes apparent that young people who resort to violence have themselves often been the victims of violence, and they often live with a profound lack of prospects, as well as social marginalisation and poverty.

According to the National Strategic Plan on Gender-based Violence & Femicide (2020), violence has been part of the South African social context for decades, rooted in historical apartheid policies and underpinned by high levels of inequality and poverty, racism, unequal gender power relations, and hostility to sexual and gender diversity.

“All of this has resulted in deep levels of collective trauma that is demonstrated in daily interactions across all social spheres as attested by the excessive homicide and crime rates.”

Chapter 12 of the National Development Plan stipulates that “gender-based violence in South Africa is unacceptably high”. The National Strategic Plan on Gender-based Violence & Femicide (NSP-GBVF) further states that while the murder rates of both men and women declined steadily between 2000 and 2015, the murder rate for women increased drastically by 117% between 2015 and 2016/17. The murder rate for men, though still higher than that of women, continued to decline between 2015 and 2016/17.

The number of women who experienced sexual offences also jumped from 31 665 in 2015/16 to 70 813 in 2016/17, which is an increase of 53%.

Police crime statistics released for the year 2018/2019, show that in Central South Africa (Free State, Northern Cape and North West) a total of 92 257 contact crimes were reported of which 9 056 were sexual offences.

According to statistics shared by Child Welfare Bloemfontein & Childline Free State, South Africa has one of the world’s highest GBV rates in the world; it is comparable to countries that are at war. Furthermore, the Crime Against Women report shows that crime against women is five times higher than the global average. The Medical Research Council estimates that one in three women in the general population have experienced physical or sexual violence at some point in their life by intimate partner.

Nearly 443 390 rape cases were reported to the South Africa Police Service over the past decade. However, it is estimated that only one in nine cases are reported. An average of 35 cases per month are reported at Tshepong Thuthuzela centres, and 41% of rape cases reported are children under age 18; 25% of girls are raped before age 16. Only 4% of cases reported result in prosecution.

The 2018 Global Peace Index noted that in economic terms, violence cost South Africa about 24% of Gross Domestic Product.

A report by the Institute for Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) estimates that the cost to South Africa of violent crime alone amounts to over R600-billion each year. Their estimate of the cost of violence includes expenditure on policing, private and state security, incarceration as well the indirect costs of imprisonment and the economic cost of murder and assault.

The IEP indicates that their estimates are conservative as they exclude items like expenditure on the judicial system, costs incurred by business, domestic violence and household out-of-pocket spending on safety.

According to the IEP, the economic cost of violence is certainly higher than the R600-billion indicated.

In terms of GDP lost, violence costs the economy almost 50% more than the global average. Of the 163 countries examined by the IEP, South Africa has the 26th highest cost of violence relative to GDP. On average violent crime costs countries 8.8% of GDP.

According to the NSP-GBVF, a costing study conducted in 2015 estimated that GBVF cost South Africa between ZAR24 - 42 billion annually, but the true impact is severely underestimated as additional social costs that compromise sexual and reproductive health, mental health, social well-being, productivity, mobility and capacity of survivors to live healthy and fulfilling lives are not fully considered.

“Violence is a traumatic event and its chronic occurrence for many women has a multiplying effect with mental health problems being the most prevalent consequence.”

Women and children who experienced GBV including rape, are at higher risk of depression, anxiety disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, suicidal thoughts and attempts. The South African Stress study found that rape was the most common reason for lifetime PTSD.

A costing study by BMJ Global Health (2018), investigating the social burden and economic impact of violence against children in South Africa, found notable reductions to mental and physical health outcomes in the population if children were prevented from experiencing violence, neglect and witnessing family violence.

The results showed, among others, that drug abuse in the entire population could be reduced by up to 14% if sexual violence against children could be prevented, self-harm could be reduced by 23% in the population if children did not experience physical violence, anxiety could be reduced by 10% if children were not emotionally abused, alcohol abuse could be reduced by 14% in women if they did not experience neglect as children, and lastly, interpersonal violence in the population could be reduced by 16% if children did not witness family violence.

The study further estimated that the cost of inaction in 2015 amounted to nearly 5% of the country’s gross domestic product. These findings show that preventing children from experiencing and witnessing violence can help to strengthen the health of a nation by ensuring children reach their full potential and drive the country’s economy and growth.

Difference between sex and gender

Before unpacking what exactly Gender-Based Violence (GBV) refers to, it is important to understand the difference between “sex” and “gender”. While people regularly substitute one for the other, their meaning and usage are significantly, and consequentially, different.

According to dictionary.com, “sex” is a label assigned at birth based on the reproductive organs you’re born with. It’s generally how we divide society into two groups, male and female—though intersex people are born with both male and female reproductive organs. (Important note: Hermaphrodite is a term that some find offensive.)

“Gender”, on the other hand, goes beyond one’s reproductive organs and includes a person’s perception, understanding, and experience of themselves and roles in society. It’s their inner sense about who they’re meant to be and how they want to interact with the world.

However, one’s gender identity and sex as assigned at birth don’t always align. For example, while someone may be born with male reproductive organs and be classified as a male at birth, their gender identity may be female or something else.

Use of the term transgender should be used appropriately though. Calling an individual a ‘transgender’ or a ‘trans’ is offensive. In other words, it should be used as an adjective (e.g., a transgender person or transgender rights).

There are also nonbinary people who don’t identify in the traditional dichotomy male or female—and indeed, everyone ranging from scientists to sociologists are understanding gender as spectrum.

The use of gender-neutral pronouns, such as “they”, should not only be considered proper grammar but also proper behaviour when referring to a nonbinary individual.

Sure, it’s easier to just put people into one of two neat boxes, male and female, boy and girl. But, humans are complex creatures, and it’s just not that simple.

The bottom line is that people deserve to be identified and referred to correctly and based on their preferences. Mixing you’re and your isn’t quite the same as conflating someone’s birth sex with their gender identity or referring to he/him/his when they prefer they/them/theirs. That causes pain and shows disrespect. So, if you have a hard time remembering how to refer to anyone, anytime, you can always call them by their chosen name. There’s no synonym for that.

Gender-Based violence

Gender-based violence (GBV) has been described as a profound and widespread problem in South Africa, impacting on almost every aspect of life. GBV (which disproportionately affects women and girls) is systemic, and deeply entrenched in institutions, cultures and traditions in South Africa.

Safer Places explain GBV occurs as a result of normative role expectations and unequal power relationships between genders in a society.

“There are many different definitions of GBV, but it can be broadly defined as ‘the general term used to capture violence that occurs as a result of the normative role expectations associated with each gender, along with the unequal power relationships between […] genders, within the context of a specific society’.”

According to the National Strategic Plan on Gender-based Violence & Femicide (2020), GBV includes physical, economic, sexual, and psychological abuse as well as rape, sexual harassment and trafficking of women for sex, and sexual exploitation.

Economic abuse, whereby financial resources are controlled and withheld, has a significant impact on the lives of women and children; often leaving them with no choice but to remain in abusive relationships. Furthermore, when women leave abusive relationships, financial abuse often continues through withholding of child maintenance.

Child Welfare Bloemfontein & Childline Free State share the difference between GBV and domestic violence:

Gender-Based Violence

- Any type of violence that is rooted in abusing unequal power between genders.

- It can include intimate partner & family violence, elder abuse, sexual violence, stalking and human trafficking.

Domestic Violence

- Intimate partner violence is abusive behaviours used by one partner to maintain power & control over other partner.

- Family violence is abusive behaviour between family members who are blood related or familial relationships.

According to Child Welfare Bloemfontein & Childline Free State, the following are warning signs of GBV:

- Extreme jealousy

- Possessiveness

- Unpredictability

- A bad temper

- Cruelty to animals

- Verbal abuse

- Extremely controlling behaviour

- Antiquated beliefs about the roles of women and men in relationships

- Forced sex or disregard of their partner's unwillingness to have sex

- Sabotage of birth control methods or refusal to honour agreed upon methods

- Blaming the victim for anything bad that happens

- Sabotage or obstruction of the victim's ability to work or attend school

- Controls all the finances

- Abuse of other family members, children or pets

- Accusations of the victim flirting with others or having an affair

- Control of what the victim wears and how they act

- Belittling the victim either privately or publicly

- Embarrassment or humiliation of the victim in front of others

- Harassment of the victim at work

Sometimes parties in an intimate relationship are not aware that their behaviour is abusive or are being abused by their partners. Take the Department of Justice quiz here.

Drivers of GBV:

- High levels of alcohol and drug abuse - SA has recently been named as having the highest level of adult per capita alcohol consumption in Africa;

- 8 out of 10 Sexual violence perpetrators are known to the victims – it is very difficult to control & report this cases;

- Many people grow up believing that violence is an acceptable way to solve disputes at home against women;

- Most violent behaviour is learned or tolerated in the home, communities and schools where children either directly experience or witness violence

- Harmful gender norms – cultural norms often dictate that men are controlling, dominant or abusive such as early forced marriage

According to the NSP-GBVF, research also shows that exposure to violence and the ideas that tolerate violence begins in childhood through how children are socialised across all settings (i.e. home, school, communities) which are reinforced by the media.

The bond between the primary caregiver (e.g., mother) and child is integral to how children form later relationships with peers, partners and their own children. “When a baby does not have a healthy bond with its caregiver, is neglected, or exposed to violence, their ability to have healthy relationships is disrupted, sometimes for generations, and their chance of being a victim or perpetrator of violence in adulthood is therefore increased.”

Childhood adversities including, physical, emotional and sexual abuse as well as neglect has been shown as a consistent driver of experiences of violence during adulthood in South Africa and other global settings.

Evidence shows that violence against children (VAC) and GBV are closely linked. The intergenerational cycle is well established from research done locally and globally, with boys more likely to perpetrate and girls more likely to become victims as adults, if they experienced childhood violence.

Changing experiences of childhood, specifically through addressing different forms of violence against children, including corporal punishment, is a fundamental basis for eradicating GBV.

According to Childline SA , child abuse can be defined as “Any interaction or lack of interaction by a parent or caretaker which results in the non-accidental harm to the child’s physical and/or developmental state.”

The term child abuse therefore includes not only the physical non-accidental injury of children, but also emotional abuse, sexual abuse and neglect. Therefore abuse can range from habitually humiliating a child to not giving the necessary care.

Recognising Child Abuse

Educators will often be the first to notice the change in behaviour of a child. This change could be the result of child abuse and it is vital that you recognise the signs and what constitutes child abuse. Read more here.

There are many myths about child abuse, for example:

- Children are usually molested by strangers;

- There is a universal taboo in all cultures about incest; men who abuse are psychotic or retarded;

- Incest only happens to girls;

- The child always feels negative towards the offender;

- Mothers know of incest and condone it;

- It does not happen in my family or community; and

- There is no love and affection in families in which abuse occurs.

According to Save the Children, the prohibition of physical and humiliating punishment is a sensitive issue and many times it is met with resistance.

The freedom of parents to choose their method of upbringing children is often seen as more important than children’s right to a life free from violence. A common excuse is that children would otherwise become bad-mannered.

Making the vision of security and freedom for children from all violence a reality demands dedication and courage from all adults who are close to children – parents, teachers, neighbours, relatives, friends and all others. When working with changing attitudes, many misconceptions are encountered based on presumed religious, cultural, parental and privacy rights.

Change starts at home. For all children, learning is an important part of growing up. In many cases, adults are learning just as much from their children as their children are from them. Parenting is never going to be easy, but it can be helped along by following some guidelines as provided by Childline SA.

Bullying is very difficult for children and adults to deal with. It makes you feel afraid and degraded and often it makes a person feel like they are worthless.

According to 1000 Women 1 Voice, South African Grade 5 pupils reported the highest occurrence of bullying out of 49 countries surveyed.

Most pupils (44%) reported being bullied “about weekly” and 34% reported being bullied “about monthly”.

Of the boys who took part in the study, 47% reported being bullied on a weekly basis. This compares to 40% of girls.

The report also highlights that pupils in South Africa’s public schools are bullied more than those in independent schools. Close to 48% of pupils in no-fee schools reported being bullied “about weekly” compared to about 25% of independent school pupils.

A 2011 Harvard School of Public Health study found that after male bullies leave school, they may turn to bullying their girlfriends and spouses instead of fellow pupils. It also found that men who had bullied schoolmates once in a while were twice as likely to have engaged in violence against a female partner within the previous year as were men who said they had never bullied their school peers.

Men who had admitted bullying frequently in school were four times as likely to have done so as were men who had never bullied in school. Thus “identification of boys who bully others (in school) may offer an opportunity to intervene on future abusive behaviours, such as intimate partner violence perpetration as adults.”

What constitutes bullying?

Bullying is repeated and intentional threats, physical assaults, and intimidation that occur when individuals or a group exert their real or perceived difference in power or strength on another.

Bullying commonly occurs in schools and can be in the shape of physical, verbal, social, or electronic aggression.

Bullying can take many forms:

- Verbal bullying — includes name-calling, threats of harm, and taunting

- Social bullying — can involve excluding someone intentionally, encouraging others to socially exclude someone, spreading rumours, or publicly shaming someone.

- Physical bullying — often results in physically harming someone or their belongings by hitting, punching, pushing, spitting, kicking, or tripping.

- Cyber bullying — involves using electronic media such as on the Internet, texting, and social media to spread hurtful and damaging stories, rumours, and images. Although cyberbullying can take place anywhere and anytime, this form of bullying often can travel rapidly through a school population and beyond, devastating the victims and leaving them feeling powerless.

Download the Department of Justice’s cyber bullying and sexting resource here.

Prevent Bullying

Students who are perceived as different by other students are more likely to be bullied. These more vulnerable students include LGBT youth, students with physical, learning, or mental health disabilities, and students who are targeted for differences in race, ethnicity, or religion.

Both students who bully and students who are bullied can suffer lasting psychological effects, including post-traumatic stress. It is vital that schools provide support to all of the students involved in a bullying incident and that schools take steps to reduce bullying.

In a trauma-informed school, the best deterrent to bullying and cyberbullying is to create a culture of acceptance and communication. Such a culture empowers students to find positive ways to resolve conflicts and has an administration, teachers, and other staff who can support students in making constructive decisions and respond proactively when aggression of any kind exists on the school campus. These steps can help you get started:

- Establish an anti-bullying policy — Know national and provincial policies and seek input from all members of your school community to determine how your school will implement rules of conduct, a way for students to report bullying, and the process by which the school will act to address reported bullying.

- Put into action a school-wide plan — Disseminate a bullying prevention plan that involves all adults on campus in knowing how to support positive behaviour, address unacceptable actions, and refer students who need additional counselling.

- Educate the school community — Incorporate bullying prevention in lesson plans, teach students how to effectively respond to bullying, and provide resources for parents so they can be partners in your anti-bullying efforts.

See 1000 Women 1 Voice’s Stop Bullying Tool Kit

Public Shaming

Rhodes Wellness College references Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, in which the character of Hester Prynne is publicly shamed for having a child out of wedlock (Clausen, 2018). Made to stand in the town square and then wear a red letter “A” on her clothes, she was forever shamed by those around her, living in isolation for the rest of her life.

Yet while Hester Prynne’s story is a fictional one, public shaming has a long and very real history. Whether making students wear a dunce cap, locking up transgressors in stockades, or parading adulterers through streets, the practice of public shaming has been followed for centuries.

In fact, public shaming has evolved in new ways with the advent of the internet. A recent survey uncovered that “66 percent of adults have witnessed online harassment while 41 percent have been victims themselves”. Among young adults, the problem is even more pronounced, given that “70 percent of young people (age 18-29) say they have experienced some form of digital hate”.

This rise in public shaming has led many experts to examine the effects it has, as well as its impact on mental health.

In his book, So You've Been Publicly Shamed, Jon Ronson tackles the phenomenon of internet-fueled public shaming, which has ruined many a career and life in an era of the enormous, and un-erasable, digital footprint.

The Child Development Institute has some tips to help you talk to your kids so they can cope with violence.

Encourage your kids to talk about what they see and hear. Tune in to your child’s feelings and encourage them to discuss what they’ve seen and heard. If your child feels depressed, angry or persecuted, it is very important to reassure them that you love them and talk about their worries.

Find out what your kids have heard at school. If needed, give them factual information to dispel any misconceptions. Give information at age appropriate levels and put events into context.

Limit exposure to violence. Research has proven that children who watch a lot of violence on TV, movies or video games feel less safe than those that don’t or it may desensitize them to violence.

Let your child know your values, for example “Violence just isn’t funny to me. I know that games and movies are not real, but when people get seriously hurt in real life it is terribly sad for everyone involved”. Watching the news and movies together provides opportunities to reinforce the consequences of violence.

Reassure your child. Kids who see or hear about violent acts can become anxious and fearful that a similar act may happen to them or a loved one. For example, you may reassure them by giving them options of what to do if they ever feel unsafe when they’re not at home. Go to a trusted adult, a teacher or family friend.

Stand firm. The values you wish to instil in your kids need to be clear and consistent. Don’t fall for the “everybody else does it” or “everyone else is allowed to watch it” trick.

Let your kids know your standards. Talk to your kids about teasing and its limits. Let them know that teasing can be bullying and can go further than what you sometimes intend. Tell them that in your family you have zero tolerance for bullying or roughhousing.

Offer tools to cope with feelings. Suggest ways that your child could cope with feelings if they are prone to getting violent. Insist the importance of using words and not being physical.

Educate your kids. Give them options and prepare them for what to do if they are faced in situations where they feel unsafe. For example, if they see a gun at a friend’s place or at school, to NEVER touch it and walk away. Tell an adult straight away as this will keep you and your friends safe.

Control your own behaviour. Examine how you approach conflict and know that your child is learning from you and may model the same behaviours.

Useful links to assist you in explaining rape to a child can be found here and here.

Attitudes and perceptions play a very important role in shaping human behaviour, including criminal activity and vulnerability to crime.

Statistics South Africa’s 2018 report, Crime against Women in South Africa, notes that attitudes towards women, driven mostly by cultural and religious beliefs, determine how women are treated in society. This includes attitudes of women about themselves. A few questions were included in the Victims of Crime Survey (VOCS) questionnaire in an attempt to capture the attitudes and perceptions of both men and women concerning violence against women, constitutional rights and crime trends in South Africa.

“An unexpected finding was that women had the same pattern of attitudes towards domestic violence as men.” The percentage of individuals who thought it was acceptable for a man to hit a woman if she argues with him, was high for both men and women respondents.

Non-progressive attitudes and beliefs among the people of South Africa, including women, remain a major challenge in fighting crime against women.

Evidence provided in this report also shows that the problem is the level of crime in the country rather than crime against women. In many crimes (including murder) men have been more victimised than women. If crime levels decline then crime against women will also decline.

This conclusion does not suggest that there is no need for targeted interventions against crimes that victimise women.

Amongst the biggest impact arising from GBVF is the enduring impact on children with violence against children and adverse childhood experiences identified as a driver for GBV.

There is increasing recognition that this context demands a whole of society approach in understanding, responding, preventing and ultimately eliminating GBVF.

Aside from various governmental interventions proposed, the NSP-GBVF further states that the private sector should be accountable for addressing GBV in the work place; Civil Society Organisations should be accountable to their stakeholders for quality of services provided and the media needs to be accountable for the implementation of ethical guidelines on how women and girls are portrayed in the media, as well as how GBVF is reported.

The Baseline Study Report for the “Teenz Alliance Project” (2017) state that sexual violence against women and girls is a multi-faceted problem and therefore a multi-sectoral approach is required to address this public health issue. “Ordinary community members themselves are important role-players in the fight against sexual and other forms of gender-based violence.”

Child Welfare Bloemfontein & Childline Free State suggest the following as a starting point to address the scourge of Gender-Based Violence:

- Motivate women to be active in civil society;

- Address unequal gender power relations;

- Volunteer at Thuthuzela One stop services for instance medical help and psychosocial support to survivors;

- Peer families approach which focuses on improving family relationships & communication skills to address social norms;

- Teach boys and men non-violence and respect for women & girls;

- Developing support programs for professionals experiencing second-hand trauma;

- Support women and children’s shelters.

A 2018 study found that in addition to providing women with emergency accommodation, shelters met women’s basic needs, provided physical and psychological safety, meeting much needed care and support for women and their children.

The study found that 75% of those who left the shelter were living free of their abusers.

However, the study also found that challenges with accessing funding often placed rural shelters at a disadvantage, thus limiting their ability to render comprehensive services and that the needs of women’s children accompanying them to shelters, were not catered for (National Strategic Plan on Gender-based Violence & Femicide, 2020).

UNWOMEN also suggest a dozen things we can practise in our lives daily to make a difference.

Twelve small actions with big impact for Generation Equality:

1. Share the care

2. Call out sexism and harassment

3. Reject the binary

4. Demand an equal work culture

5. Exercise your political rights

6. Shop responsibly

7. Amplify feminist books, movies and more

8. Teach girls their worth

9. Challenge what it means to “be a man”

10. Commit to a cause

11. Challenge beauty standards

12. Respect the choices of others

Domestic violence – what can the workplace do?

The TEARS Foundation suggests that every workplace can make a significant difference to the safety and well-being of victims of domestic violence and their co-workers by introducing domestic violence clauses into enterprise agreements. The following are recommendations of existing policies and procedures.

Join and support international, national and local campaigns like the 16 Days Campaign. The 16 Days of Activism for No Violence against Women and Children Campaign is a United Nations campaign which takes place annually from 25 November (International Day of No Violence against Women) to 10 December (International Human Rights Day).

What is consent?

Advocacy group, WISE 4 AFRIKA, explains In order for any sexual interaction to take place, there must be consent. Without consent, sexual contact is assault.

Read more here.

Guidelines on what to expect when you report a sexual offence to the police.

Department of Health uniform national health guidelines for dealing with survivors of rape and other sexual offences.

When laying a charge you have the following rights:

- The right to be treated with fairness, and with respect for dignity and privacy

- The right to offer information

- The right to receive information

- The right to protection

- The right to assistance

- The right to compensation

- The right to restitution

All victims must be treated with fairness, respect and courtesy, in private, without discrimination, regardless of circumstances, population group, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation and appearance.

Find out more here.

Children’s Rights

Section 28 of the Bill of Rights, entitled "Children", says every child has the right to:

- A name and a nationality from birth.

- Family care or parental care, or to appropriate alternative care when removed from the family environment.

- Basic nutrition, shelter, basic health care services and social services.

- Be protected from maltreatment, neglect, abuse or degradation.

- Be protected from exploitative labour practices.

- Not be required or permitted to perform work or provide services that are inappropriate for a person of that child's age or risk the child's well-being, education, physical or mental health or spiritual, moral or social development.

- Not be detained except as a measure of last resort, in which case, in addition to the rights a child enjoys under sections 12 and 35, the child may be detained only for the shortest appropriate period of time, and has the right to be kept separately from detained persons over the age of 18 years.

- Be treated in a manner, and kept in conditions, that take account of the child's age and have a legal practitioner assigned to the child by the state, and at state expense, in civil proceedings affecting the child, if substantial injustice would otherwise result.

- Not be used directly in armed conflict, and to be protected in times of armed conflict.

Chapter 2 of our Constitution contains the Bill of Rights which applies to everyone. Some of these rights apply to children and should be exercised responsibly. These include:

- The right to family care, love and protection and the responsibility to show love, respect and caring to others especially the elderly.

- The right to a clean environment and the responsibility to take care of their environment by cleaning the space they live in.

- A right to food and the responsibility not to be wasteful.

- A right to good quality education and the responsibility to learn and respect their teachers and peers.

- A right to quality medical care and the responsibility to take care of themselves and protect themselves from irresponsible exposure to diseases such as HIV/Aids.

- A right to protection from exploitation and neglect and the responsibility to report abuse and exploitation.

Download a child-friendly version of the rights here.

Find out more about the Child Justice Act here.

Below is a list of contacts and resources that could be useful in a crisis situation.

- SAPS Emergency Number

10111

- SAPS, GBVF-related service Complaints

0800 333 177

0800 428 428

- STOP Gender Violence Helpline

0800 150 150/ *120*7867#

- Halt Elder Abuse Line (Heal) – helpline for elderly people

0800 003 081

E-mail: action@actiononelderabusesa.co.za

- Human Trafficking Helpline

08000 737 283 (08000 rescue) / 082 455 3664

Lockdown Counselling Number

076 694 5911 (The counsellor is available from 08:30 – 16:30, Monday to Sunday.)

010 590 5920 or 24/7 free call: *134*7355#

- Childline South Africa Children can speak to a counsellor, 24/7, free from all networks. 116 or 0800 55 555

087 822 1516

E-mail: national@childwelfaresa.org.za

011 484 4554 (Office hours only)

(011) 975 7106/7

E-mail: national@famsa.org.za

- LifeLine South Africa

27/4 Counselling Number: 0861 322 322

Suicide Crisis Line

0800 567 567

SADAG Mental Health Line

011 234 4837

Dr Reddy's Help Line

0800 21 22 23

Cipla 24hr Mental Health Helpline

0800 456 789

Pharmadynamics Police &Trauma Line

0800 20 50 26

Adcock Ingram Depression and Anxiety Helpline

0800 70 80 90

ADHD Helpline

0800 55 44 33

Department of Social Development Substance Abuse Line 24hr helpline

0800 12 13 14

SMS 32312

Akeso Psychiatric Response Unit 24 Hour

0861 435 787

Cipla Whatsapp Chat Line

076 882 2775

- Information on teen suicide prevention

- Helping someone who is depressed

- What to do if you are raped

- What happens when you report a rape or other sexual offence?

- Myths about rape

- Rape-Trauma-Syndrome

- Supporting someone who has been raped

- Basic facts about women abuse

- Safety plan to escape domestic abuse situation

Shelters:

Free State:

- Bethlehem

Child & Family Welfare

Tel: 058 717 3999

Email: ksorgbhm@bcfw.org.za

- Parys

Tumahole Victim Support Centre

Tel: 056 819 8881

Email: motlalepule.pule@gmail.com

- QwaQwa

Thusanang Advice Centre Shelter

Tel: 058 713 6074

Email: tadvice@telkomsa.net

- Welkom

Goldfields Family Advice Organisation

Tel: 057 396 6153

Email: lekalese@webmail.co.za

Vaal:

- Sedibeng

Bella Maria

Tel: 016 428 1640

Email: colleen@lifelinevaal.co.za

Northern Cape:

- De Aar

Ethembeni Community & Trauma Centre

Tel: 053 631 4379

Email: ectc@telkomsa.net

- Upington

Bopanang One Stop Centre

Tel: 054 332 3876

Email: cvoss@ncpg.gov.za

- Kimberley

Kimberley Shelter

Tel: 053 874 9263

Email: PQondani@ncpg.gov.za

North West:

- Mooi Nooi

Grace Help Shelter

Tel: 014 574 3476

Email: gracecentre@mweb.co.za

Trauma Counselling and Support:

- LifeLine Free State

Crisis: (057) 352-2212

- LifeLine Vaal Triangle

Crisis: (016) 428-1640

Office: (016) 428-1740

- LifeLine Mafikeng

Crisis: (0183) 814-263

- LifeLine Klerksdorp

Crisis: (018) 462-1234

- LifeLine Rustenburg

Crisis: 0861 322 322

Thuthuzela Care Centres:

Thuthuzela Centres (TCCs) are one-stop facilities that have been introduced as a critical part of South Africa’s anti-rape strategy, aiming to reduce secondary victimisation and to build a case ready for successful prosecution. Fifty one centres have been established since 2006.

Free State:

- Welkom

Bongani TCC

Health Complex (Old Provincial Hospital)

Long Road

Tel: 057 355 4106

- Sasolburg

Metsimaholo TCC

Metsimaholo District Hospital

8 Langenhoven,

Tel: 016 973 3997

- Bethlehem

Phekolong TCC

Phekolong Hospital

2117 Riemland Road, Bohlokong

Tel: 058 304 3023

- Bloemfontein

Tshepong TCC

National District Hospital

Roth Avenue, Willows

Tel: 051 448 6023

Northern Cape:

- De Aar

De Aar TCC

Central Karoo Hospital

Tel: 053 631 7093 / 053 631 2123

- Galeshewe

Galeshewe TCC

Galeshewe Day Hospital, Tyson Road

Tel: 053 830 8900

- Kuruman

Kuruman TCC

Kuruman Hospital, Main Street

Tel: 053 712 8133

- Springbok

Springbok TCC

Van Niekerk Hospital, (Springbok Hospital)

Hospital Street,

Tel: 027 712 1551

North West:

- Rustenburg

Job Shimankana Tabane TCC

Job Shimankana Tabane Hospital, Cnr Bosch & Heystek St

Tel: 014 590 5474

- Klerksdorp

Klerksdorp TCC

Klerksdorp Hospital, Benji Oliphant Road Jouberton

Tel: 018 465 2828

- Mafikeng

Mafikeng TCC

Mafikeng Provincial Hospital, Lichtenburg Road

Tel: 018 383 7000

- Potchefstroom

Potchefstroom TCC

Potchefstroom Hospital, Cnr Botha & Chris Hani Street

Tel: 018 293 4659

- Taung

Taung TCC

Taung District Hospital, Office 005 Trauma Counseling Unit

Tel: 053 994 1206

Find more centres here.

More Organisations Rendering Assistance:

Free State:

4 Aliwal Street, Arboretum, Bloemfontein

Tel: 051 430 3311

Email: admin@cwcl.org.za

Northern Cape:

40 Synagogue Street, Belgravia, Kimberley

Tel: 053 831 5504

- Optimystic Bikers against Abuse, Kimberley

Whatsapp or call 071 427 0187, sos@optimystic.za.net.

North West:

91 Chris Hani Street, Miederpark

Tel: 018 293-0425

Email: admin@childwpotch.co.za

Tel: 014 556 1722 / 078 888 4937

Satellite Offices:

Direpotsane Street Phokeng (Police Station)

Tel: 014 566 1722

Boitekong Police Station

Tel: 082 733 1929

Mfidikwe Clinic

Tel: 082 491 7055

- Thusanang Home-Based Care

839 Old Municipality Building, Koboyapodi Street, Reivilo

Tel: 079 565 2503 / 071 926 2059

- Sirologang Trauma Relief

Office 3, Ganyesa Police Station

Tel: 073 569 3753 / 072 959 1725

Email: oatiroeng@gmail.com

Dealing with Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Dealing with anxiety.

Managing your anger.

Handling aggression.

Please note, some of the content shared below may be graphic in nature and is not intended for sensitive viewers or listeners. The intention is to provide a platform for survivors and activists to educate and inspire positive action.